Venture’s Journey Into Private Equity

This content originally appeared on Forbes.com

Will VCs develop their own private equity capabilities as a means of driving more exits int their portfolios? As published originally on Forbes, the numbers present a compelling case for why this might happen.

We’ve seen recently that a number of venture firms are looking to acquire mature businesses and apply AI to drive growth and efficiency. That speaks to the opportunity that we see in this latest revolution, and we expect to see more of this type of activity going forward. While much of the reporting has focused on this as a reason for VCs to enter private equity, I also see a structural aspect of venture that I believe will compel firms to move into private equity; namely, the structural imbalance between the number of startups that venture firms have invested in relative to the rate at which these are being acquired.

To set the stage, recall that the best companies in venture drive the majority of returns in the industry. The attempt to invest in and build those companies - which typically scale past $100mm in ARR and keep growing with increasingly efficient unit economics - has led VCs to fund a significant number of companies.

A query of PitchBook’s data shows over 54k VC-backed companies in existence in the US, with 28k seed companies, 14k series A companies, 6k series B companies, 2.8k series C companies, and 1.2k series D companies as of May 2025. Contrast the sizable inventory of startups with the more tempered pace at which exits are happening as seen in the graph above, showing the number of exits by stage for VC-backed companies over the last decade.

How Long Could it Take to See VC-Backed Companies Exit?

If we contrast the inventory of companies with the number of exits at their respective stages, this has averaged over the last decade around 200 Series A company exits per year, 130 Series B company exits per year, 80 Series C company exits per year, and 90 Series D (or later) company exits per year. At that rate, considering just the most mature companies at the Series D stage, we would need about 1.2k / 90 = 13 years for these companies to exit. If we look at the inventory of current Series C stage companies, the historic exit rate would imply roughly 35 years to remove the backlog of VC-backed companies.

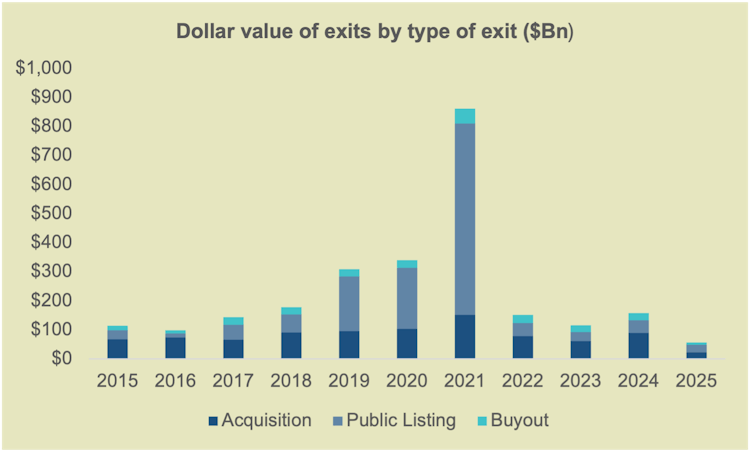

Exits for startups typically come from getting acquired by a strategic or a private equity fund or going public. When looking at the distribution of exit types, we find that the average exit path over the last 10 years has been 73% acquisition, 19% buyout by a private equity firm, and 8% IPO. In past analyses, we’ve also seen that a meaningful percentage of startups at each stage either go out of business or continue on as private companies without raising subsequent rounds of financing.

If the volume of exits is not there, could the values associated with exits tell us something different? What we look at exits by dollar value, we find that the source of the best returns - the IPO market - has been effectively closed the last few years. IPOs generate the best outcomes in terms of total market capitalization, but the window at this point has closed for all but the largest startups.

What Happens Next?

Given the longer hold time for companies, we’ve already seen venture firms exercising fund extension rights with limited partners as well as establishing continuation funds to keep investing in portfolio companies. We’ve also seen venture firms increasingly look to sell stakes in their portfolio companies to secondary buyers as a way to generate distributions to limited partners.

The problem with these solutions is that they don’t match the scale of the inventory of good companies that exist. I believe that the natural evolution of venture will be to build out private-equity-like capabilities, whether through the addition of teams with PE experience or by raising funds specifically focused on rollup strategies. In effect, venture funds will move to a model where they can sponsor their existing companies to grow through acquisitions and drive scale and efficiency.

For entrepreneurs, this means that the exit strategy could increasingly be a focus on identifying complementary startups that they can merge with as part of this evolution. This trend has already begun over the last several years, and may become a meaningful exit path as venture funds increasingly look to drive scale and ultimately exits for their portfolio companies.

This is by no means an easy path, however. Venture companies tend to be concentrated in waves. At one point in the past we had identified at least 29 venture-funded antivirus software companies competing for that market. Today we see similar volumes of new companies being funded in similar markets in the current wave of AI companies. Building and scaling defensible data or distribution strategies and meaningful market shares will be required for this type of transition into more of a private equity-type model to work. We expect to see operators from private equity firms be brought onboard by the larger venture funds given the scale of the capital tied up in their portfolios over time. We’ve already seen investment bankers hired into capital markets or advisory roles at the larger funds, and I believe this type of rollup persona will become increasingly common in the years ahead. While there are plenty of opportunities to buy mature companies and drive efficiencies via AI, I believe the imbalance between the supply of good companies versus the volume of exits will by itself drive the transformation of our industry.

Japan-U.S. Startup Ecosystem Roundup

Join us for a Japan-U.S. Startup Ecosystem Roundup, exploring the latest policy and market-driven opportunities for cross-border startup growth.

Designed for investors and corporates engaging with startups, the event will feature key voices in Japan-U.S. innovation.

Are Megafunds Warping the Venture Market?

Megafunds aggressive early-stage participation is inflating competition and valuations, forcing smaller firms to adapt while raising concerns about returns.

AI on Both Sides of the Table

How founders use AI to pitch and update—and how investors are using the same tools to judge them